Run To Win Sample Chapter

The

Race That Changed What I Believe Is Possible In Life

This is one of 14 chapters in my new book, Run To Win.

MANY GREAT THINGS HAD HAPPENED when I was nearing the end of my running career, yet there were also some unfulfilled expectations.

In 1983, I qualified for and ran in the 1983 USA Track and Field Championships in Indianapolis, IN.

At the 1983 USA Track

and Field Championships, my heat to get to the final was brutal. My heat had powerful

competitors like Olympians Steve Scott and Steve Lacy. Steve Scott was the American record holder in

the mile at 3:47. He won the silver medal in the 1500 meters in the world

championships.

Steve Lacy was another fast runner who ultimately made the Olympic team in 1980 and 1984. Other fast runners included Craig Masback, Chuck Aragon, and Tom Smith – also in my heat – and all capable of running well under a sub-4-minute mile.

Unfortunately, I did not make the final that year. However, I made significant progress in 1983. I was inspired to run in the same heat with the guys I looked up to at the time. Running in the same heat with some of the best in the USA and the world at the time gave me the motivation to keep exploring how to become better by running faster.

To even be eligible for

the USA Championships (The TAC Championships back then), you had to run the

1500-meter equivalent of about a 4:00 mile in a qualifying race to compete. I

ran my only track mile in 4:00.10 that year to qualify.

Given my success in 1983, though, I was encouraged to train for the Olympic Trials 1984, but I got injured. I remember finishing my last 1500-meter race after missing several weeks of training. It was apparent that I had lost a lot of fitness.

My season, and ultimately my career (or so I thought), was over as I wasn’t going back to a USA championship event again.

I once heard the phrase, “that frustration simply means you have not found a way to reach a goal yet.” I was frustrated with my running performance as a young adult as the twilight of my career approached.

I had reached the semi-finals of the 1500 meters at the USA Track and Field Championships, was a two-time Big Sky 800-meter champion, held my University and conference 800-meter record, and ran a solid mile in my 20s, an event I rarely ran in college or as a post-collegiate athlete.

I had reached the national class level as a post-collegiate athlete but knew deep down inside that I was not running to my God-given potential. I never trained for the 100 meters as an adult running it just once in 11.07 electronic, without ever preparing for the event.

For you non-runners, that is a pretty good speed for a distance runner, especially back in the stone age when I ran.

I was starting to learn to listen to my intuition more. I knew deep down inside that I had more in the tank to give, primarily because of the unusual speed for a mid and long-distance runner.

Because I had also run in the 47s on 4x400 relay splits in college and was a good sprinter in my youth, I knew somehow I could run faster in the mile upward. The question was how.

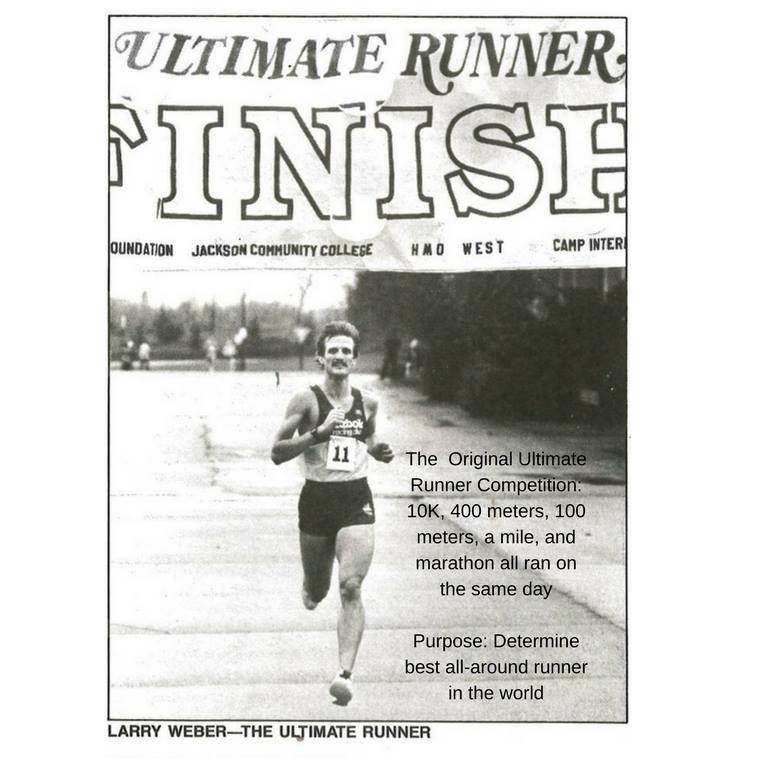

The Original Ultimate Runner Competition Answered The Question

As stated above, I was a nationally ranked miler by my 20s. However, aging legs are not a national class runner's friend. It was nearly time to hang up my spikes and move to the following chapters of life. I wanted to know if I could become a world-class runner before giving up on my running dreams. The Olympic dream I had in my youth was gone, but could I give it one last shot to somehow run with the best in the world?

I found the answer to my question in the original Ultimate Runner Competition.

The Original Ultimate Runner Competition seemed to suit my giftings—I could run all the events well like a world-class decathlete, but I had not attained world-class status in any running event. I was still unsure why I had not reached my goal and wanted to know the why behind my frustration, so I didn’t look back and say, “what if.”

But … I didn’t look back and say, “what if.” That was the nagging question – how would I feel about reaching my potential if I took a pass on this event?

Life Lesson # 1: Give yourself one last chance to reach a worthwhile goal. If ten years from now, you can see yourself wondering – what would have happened if I had tried that … then just do it if it is safe and feasible to do so!

When I saw the original Ultimate Runner Competition advertisement in a national running magazine, I jumped at the chance to compete. The race seemed like climbing Mt. Everest to me at the time. It was the battle and adventure I was looking for at the time.

The original Ultimate Runner Competition consisted of running a 10k, 400 meters, 100 meters, mile, and a marathon all on the same day. Some of the world's best runners at various distances gathered to compete in The Ultimate Runner Competition to determine the best all-around runner.

The original Ultimate Runner Competition sought to answer these questions: Was a miler or middle-distance runner the best runner in the world? Was a sprinter the best in the world? Was a marathon runner or ultra-marathon runner the best runner in the world?

The original Ultimate Runner Competition winner was honored as the best all-around runner, much like track and field honors, the Olympic decathlon winner as the best all-around athlete in the world, and the Iron Man determined as the best triathlete in the world.

The original Ultimate Runner Competition was founded to test the limits of human endurance in one day. The founders of the race reached their goal. The original Ultimate Runner Competition (it no longer exists) was the most challenging and brutal endurance test and event by far in my lifetime.

The race ended in its original form probably due to how hard it was to complete it and organize it logistically.

Runner's World Magazine writer Jim Harmon covered the race one year and had this to say about The Ultimate Runner: "This competition may be the last word in running endurance."

Imagine running at nearly top speed for over 33 miles in one day for a moment. As any runner knows, running in and out of oxygen debt is painful in just one workout. Imagine doing this for an entire day over a total distance of 33 miles!

Running 33 miles fast in five different races is a pain level I

had never experienced before or after this race.

Starting Over Again With A Blank Piece Of Paper

So, how do you train for a 10k, 400 meters, 100 meters, a mile, and a marathon in one day? How do you develop your speed without killing it with all the miles required to run a marathon?

How do you create a new training roadmap for something where none exists?

The Ultimate Runner Competition forced me to coach myself and develop an entirely new plan for training.

There was no blueprint for running a 10k, 400 meters, 100

meters, a mile, or a marathon all in one day. Nothing close existed to a

training plan for this event.

I had to throw out much of what I knew about training and start from scratch. The simple strategy of starting over again in my internship gave me many new insights.

So, with about a year to train for this event, I created a new training road map through trial and error.

The experience of creating a new training plan for the ultimate runner and learning by doing through trial and error proved to be a bit prophetic for the rest of my life story. I’ll share more about how this approach to learning had profound impacts on my life later in the book.

The first thing I did to train for this event was to read all the best evidence-based training research I could get my hands on at the time for mid and long-distance running. I devoured books on the subject.

I kept an open mind about changing the sacred cows of training that

I knew at the time. After much best practice research, I started including new

training strategies that were not a part of my training plans in the past.

Changing how things are currently done is usually hard for people to hear and do. Entire books are written about how to change the status quo. For some reason, I embraced change and truly saw this new race as a new and exciting adventure. I had to prepare for my new journey well.

New Discoveries And Lessons Learned

After analyzing my current training and conducting much research, I discovered that I had never included lactate threshold training in my training. Now, they did not call it lactate threshold training at the time. More common terms at the time included steady-state running or fast hard runs.

For you non-runners, running at your lactate threshold is a pace that you can hold roughly for a half marathon. It helps you improve your endurance, meaning you can hold a stronger pace for a more extended period.

You break up your training with runs at this pace from 20 to 40

minutes segments or more if you are a marathon runner. I am simplifying the

idea behind lactate threshold training here for non-runners, but my explanation

is the gist of what it entails.

Other significant things I changed in my training included running well over 2 hours in a single run to activate various physiological changes I was learning about, shorter 30s, 60s, and other sprints for speed, and other training methods outside of this book’s scope. Someday, I’ll share more details about my training for this event.

The critical point in my journey: I challenged status-quo thinking, the way things are done today, because as I was learning at the time, there is always a better way.

The big idea I learned through coaching was to analyze your current situation, question why you are doing what you do, and see if there is a better way. And, don’t be afraid to challenge the status quo, the current way of doing things.

I even started coaching others at this time based on my research, even though I had no formal coaching credentials or certifications. Unknown to me at the time, this approach to life would also become a life-long paradigm.

Some of the people I coached in that era qualified for the USA Olympic Trials in the marathon and won marathons, so the training I was giving worked well for them.

And as I tested my fitness, I saw good results in my training.

In a race in 1985 called the Main Street Mile, I took the lead with 100 meters to go. Gary Gustafson, a 3:58 miler on the track and a USA finalist at 1500 meters, passed me with about 30 meters to go.

Gary ran 3:51.4, and I ran 3:52.1 for the entire mile on a certified mile course with an elevation loss. The course was smoking fast and later became the site of the USA Master’s National Road Mile Championships.

The point of bringing this up is that I was getting in better

shape than ever before from a speed and endurance standpoint. The Main

Street Mile race and one “test” of my training endurance fired me up to train even

more challenging for the original Ultimate Runner Competition.

While training for the Ultimate Runner, I ran a certified road 10k in Arizona in a time of 29:34 called the KOY Classic, Phoenix 10k.

I had never explicitly trained for the 10k in my career, so this was a good time for a mid-distance runner.

To put my time in perspective to non-runners, I could see Bill Rodgers, the four-time Boston Marathon champion finishing roughly 150 meters ahead of me because of the long stretch to the finish line.

Many other of the best 10k runners in America also ran and

finished ahead of me in the race, but I saw the glass half full because I was

sprinting at the end, had a lot left in the tank, and passed people as I

charged the finish line.

I was getting strong and fast as I prepared for the Ultimate Runner in the early fall of 1985. I had never run a road 10k that fast before.

I remember thinking to myself immediately after the race that I should have run faster in the middle because I had so much left at the finish line—another good sign. And much more importantly, I was beginning to believe in my new training.

And, I figured it wasn’t

too bad to be that close to a multiple Boston Marathon champion and other great

American and other 10k runners in a race

I did not usually run in that era.

However, I still needed to prove my new training theories by testing what I thought to be true in my upcoming race. The ultimate test of the changes to my training was about to happen.

I learned new lessons about stepping out in faith and challenging the status quo that would serve me well in the following chapters of life.

So, what happened with all this new training and my new philosophies on the actual ultimate runner race day?

The proof is always in the pudding, as they say. I will share the detailed results of the Original Ultimate Runner Competition outcome in the next chapter.

Primary Insight: Positively challenging the status quo is the first step in transformational change. Don’t be afraid to experiment and take calculated risks to improve your performance. Nearly all breakthroughs in life require thinking differently from established processes. There is almost always a better way.